Chapter 4: On the frontline of policing in London

Frontline officers are based in one of twelve Basic Command Units (BCUs). These were established in 2018 as part of the austerity measures. Prior to this there were 32 Borough Operational Command Units (OCUs), one for each London borough. "Five BCUs cover two London boroughs, six cover three, and one BCU covers four." [p107]. So they cover a much wider area that the OCUs. They have the same structure and level of resourcing with limited variation, and have five teams:

- Emergency Response and Patrol Teams (ERPT, often known as ‘Response’ or ‘Team’), providing emergency response to 999 and local patrols

- Neighbourhood Teams, which are the community policing function, providing beat officers dedicated to particular wards, safer schools officers, and youth engagement. These are frequently referred to as Safer Neighbourhoods Teams, the name of their predecessors

- CID (Criminal Investigation Departments), which are the detective units investigating crimes including burglary, robbery, serious assaults, gangs and organised crime, and which run offender management and youth offending programmes as part of multi-agency Youth Offending Teams

- Public Protection, which are also detective units, covering crimes of domestic abuse, child abuse, online abuse, sexual exploitation, rape and sexual assaults. Chapter 5 examines Public Protection in more detail

- HQ, which provide the non-operational work on the BCU, including professional standards, co-ordination functions, facilities and communications. [p107]

In 2021 Town Centre Teams were introduced within the Neighbourhood team function "to provide a visible and reassuring presence in areas of high footfall." [p107]

There are some pan-London teams, such as the Violent Crime Task Force (VCTF), the Territorial Support Group (TSG) and Armed Response (MO19) who respond to particular incidents. But the officers in the BCUs are the ones that most people will interact with most of the time. "The BCU is the face of local policing." [p108].

In 2021-22 about 40% of Met employees worked in BCUs. Interestingly, and possibly reflecting the fact they are the least prestigious placements, they have higher numbers of women and members of ethnic minority communities than other parts of the Met. The number of frontline officers is about the same as they were a decade ago, though there was a decrease in 2018-2019 (I think this was due to austerity cuts but cba to check).

However, the number of civilian staff in BCUs has fallen dramatically, from 2,422 in 2012-13 to 409 in 2022. Frontline PCSO numbers have also fallen massively, from 2,401 in 2012-13 to 668 in 2021-22, as have Special Constables which have gone from 4,882 in 2012-13 to 1,587 in 2021-22 (and who, remember, are volunteers and unpaid, and thus shouldn't be affected by budget cuts and if anything you'd expect their numbers to increase).

So while the number of officers on BCUs is much the same as it was ten years ago, the overall number of people working in local policing has fallen by 6,772 (from 28,254 to 21,482) or the equivalent of around four BCUs worth of people.

In the period around 2015, there was a particularly sharp decline in officers on the frontline and overall frontline workforce numbers continued to fall until 2019. It should be noted too that, prior to 2018, staff investigating child abuse and rape and sexual assaults were in a specialist command and were therefore not included in the officer count. [my emphasis, p110]

The report notes,

A proportion of the civilian posts (such as crime and performance analysts) were centralised in order to save money rather than being lost. But due to the subsequent outsourcing of functions such as human resources, we have been unable to assess what that proportion was. [p110]

The review visited every BCU. They found people who took pride in their work and were trying to serve their communities but were overstretched, under-resourced and ignored by those in charge

Long standing officers said that BCUs have always suffered from the comparison with specialist functions, but that their status as the poor relation had become more pronounced over the past five years.

There are no longer staff canteens across the Met to provide hot meals on shift. Rotas are constantly changing. Officers arrive for their eight hour shift to be told they will be doing a 12 hour shift instead. PCSOs wait six months for a uniform. Public Protection officers buy boxes of tissues for victims. Fridges and freezers containing rape forensic samples are iced up and taped shut. [my emphasis, p111-112]

The comparison between BCUs and the specialist teams is stark.

These specialist units remain comparatively well-resourced, well-trained and well-supported, with good facilities, and experienced officers and staff. On arrival in one specialist OCU, the Review team were shown around to see the set-up, admire the kit, the gym, and the special operations rooms. This never happened on a BCU visit. p112

This is a key line that should be given far more attention by those writing about the report,

Austerity was imposed on the Met, but the leadership made choices about where these cuts fell, and local policing has suffered most. [p113]

Good staff are constantly firefighting and bad staff are allowed to do f.ck-all because there's a lack of oversight. The lack of oversight also affects good officers. One anonymous contributor said,

There’s no performance management...(I) don’t know if I’m doing a good job or not.” [p115]

The report examines the 'churn' that BCUs experience - the total number of people leaving and joining teams. They foiund that the churn rate for 2021-22 was 45%, compared to 18% in Firearms Commands and 21% in MO7.

One of the problems is that the BCU resourcing takes no account of local issues.

For example, the resourcing model in South East (Bexley, Lewisham, Greenwich) is much the same as Central North (Camden and Islington). But there are over 50% more sexual offences in South East as there are in Central North and more than twice as many domestic abuse offences. Population numbers also vary significantly between BCU areas, with the population of North West BCU (Brent, Harrow, Barnet) nearly twice that of Central West (Westminster, Kensington and Chelsea, and Hammersmith and Fulham). [p116]

The report also points out that this resource model is five years old, so even if it resources were distributed correctly when created, the model is outdated and needs review.

This mismatch in resources and need was also pointed out by

a report by His Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services which found,

Some BCUs investigate higher numbers of RASSO [rape and serious sexual offences] than others but have similar supervisor numbers. The force recently created an additional RASSO inspector post for every BCU regardless of the demand each unit was facing. This isn’t matching resource to demand or providing the right support to staff. [p116]

The Casey report concludes,

This reflects a wider issue of poor resource and demand understanding across the Met highlighted in this report, but in practical terms it means that on BCUs, Response teams are being run beyond their real capacity. [p117]

The lack of appropriate resourcing has led to BCUs being severely understaffed.

One officer told us of a late-turn shift with one trainee detective on shift to cover two London boroughs. [p117]

In one of the Met's numerous initiatives, Response teams became responsible for all non-complex crimes in 2018.

This was designed to encourage officers on Response to ‘get it right first time’, meaning to undertake the necessary inquiries and paperwork to deal with a crime, and not hand it over to another team. Mi-Investigation, as it is called, was well intentioned but not thought through and has become universally unpopular. [p117]

As seems to be so often the case, BCUs developed their own ad-hoc schemes to address this extra workload. However, this then reduced the number of officers available to do the actual job of the Response team (though it seems it was very much a damned if you do, damned if you don't situation).

The tendency for the Met to set up new teams in response to delivery gaps or to show action is being taken on a particular issue created further pressures. Whenever a new team or taskforce is set up, the officers to staff this are drawn from BCUs...

An intranet comment noted:

“The Met's solution to crime has always been to create these squads to appease the government with ‘this is what we are doing’ ‘setting up another squad’ to tackle an issue when it's never a real solution.”

[p118]

One significant problem is that the number of staff "on paper rarely matched who was actually available." [p119]

Aside from holidays and sick leave, the main reason for this was that staff are "abstracted for 'Aid'" [p119].

One major reason is that staff on BCUs are abstracted for ‘Aid’. That means they are providing policing elsewhere in London for demonstrations, football matches or large public events... This is a long-standing practice. But the now-threadbare resourcing model, along with the impact of changes in demand, leaves a lot of understaffing for the day job while requests for Aid are met. [p119]

A Response team from a BCU will be called on to provide 'Aid', so then other teams get called on to staff up Response and it all just sounds an absolute mess. Neighbourhood Policing teams are supposed to be ring-fenced from being called to 'Aid' but are constantly being called on to fill in gaps on other teams, leading officers to rarely work in their actual designated BCU.

An officer described having no time to arrange meetings on her patch because she was so often pulled to Aid and to other teams that had already been abstracted.... Another said that, in the year he spent nominally on Neighbourhoods, he only spent about two and a half months actually working on a ward, as he was always sent to staff up other teams... [An Inspector] said backfilling other teams and abstractions meant the cancellation of key Met priorities:

“Women invited as part of the Walk and Talk initiative had their event cancelled as officers had to be used on Team.” [p119-120]

Their is a hierarchy but due to the understaffing of BCUs the entire hierarchy gets called in to provide Aid, with no consideration to the impact on the work they are supposed to be doing or the mental well-being of staff:

The Review was given an example where a Detective was mid-way through a long and difficult rape trial in Crown Court lasting two weeks. Over the weekend in the middle, they were instructed to report for Aid duty and spent the weekend in a police station waiting to be called to action. No one had seemed able to see how this would potentially undermine the Detective’s ability to work well during the rape trial. To her, no one seemed to care. pp121]

In contrast, specialist teams are actually ring-fenced and aren't part of the Aid hierarchy.

A recent paper for the Management Board estimated that across the Met, around one in four officers are not fully deployable. It indicated that the impact is particularly acute in local policing... The paper explained that this information is not recorded on management systems, so BCUs will appear to have the right level of resource, when they are actually operating at around 20-25% below this figure. [p121-122]

This has led to the significant increase in overtime noted in

Chapter 2 but even that isn't sufficient to enable officers to keep on top of their workload.

Many officers find that working unpaid, late and on their days off, is the only way to even come close to keeping up with their workloads. Although this was particularly the case for detectives, many officers on Response would remain at work late to complete their paperwork or ensure a case was handed over properly. [p122]

This is particularly acute in those investigating rape and serious sexual offences, with 80.3% 'often' working in their free time.

The report describes how this understaffing is exacerbated by the high percentage of staff who are inexperienced.

On average, in BCUs, 25% of all Constables and 45% of Detective Constables are probationers (Police Constables and Detective Constables with less than 2 years’ experience)... There is a knock-on effect. As fast as new recruits come in, more Sergeants are needed to supervise them and so they too are increasingly less experienced. [p123]

Despite actively recruiting new officers,

...the Met almost seems to have been taken by surprise by the arrival of new recruits. The active recruitment drive should have prompted the Met to review how they could best support new recruits, embed good behaviour and standards and treatment of the public, and generally maximise supervisory and management oversight... However, some policies and practices seemed to actively counteract support and oversight for new recruits. [123]

The problems described in

Chapter 3 regarding poor supervision and management are particularly evident in frontline policing.

The number of PCs who were to be managed by a Sergeant – ‘supervisory spans’ – was increased in 2018 as part of cost saving measures from 1:8 to 1:10. When the new policing model was adopted, these ratios were one of the ‘red lines’ with no flexibility.

This clearly presents risks, but may be manageable if there are experienced Constables, Sergeants and Inspectors above them. But with 4,557 new recruits coming in over three years, those risks clearly increased. Yet no change was made to the supervisory spans. If anything, they have expanded further, with several officers telling us the ratio was now more often 1:12. This has left Sergeants and Inspectors carrying greater and greater risk. [p126]

The impact on the culture of BCUs is clear,

We were told repeatedly that the Sergeant rank is the most critical for instilling and enforcing culture and values. But at a time when culture and values are being questioned, supervisors are not being given the tools to deliver this important role.

The primacy of hitting number targets at both PC and then Sergeant levels – emphasising quantity over quality – and the apparent absence of strategic planning in meeting the supervisory needs of new recruits has left officers at all levels under- prepared for the jobs they are expected to do. [p126]

The report notes that supervisory spans are much lower in specialist unit and that,

This is one of many examples where those parts of the Met that are closest to Londoners are not valued in the way that the more specialist teams are. pp127]

The loss of civilian staff and support services resulted in a loss of the "'glue' that makes policing effective." [p127] Many intelligence analysts have been lost. These analysts "are involved in proactive and reactive operations and tackle emerging areas of risk and harm." [p127] There is supposed to be a lead analyst for each BCUs and 48 intelligence analysts across the 12 BCUs. However, it is rare that all 12 lead analyst positions are filled at any one time. This means "a loss of fine-grained analysis at the local levels" [p127] that makes proactive policing much harder. It seems that no-one thought this was a good idea, it was just cheaper.

The same can be said for HR and welfare services, occupational health and finance, which has either been centralised or outsourced. Yet again we see BCUs trying to DIY solutions to this loss of services:

Officers felt that remote HR support lacked the context to support officers managing locally. As a result, some BCUs had developed their own services, using warranted officers to perform roles which used to be undertaken by civilian staff. These roles could be better performed by a trained specialist while warranted officers might be better deployed on the frontline.

At least one BCU Commander had set up a programme to try to bring officers who had been on recuperative duties for some time into more suitable roles. No help had been forthcoming from the centre. A Superintendent co-opted a PC who had previously worked in HR to use her skills for the project. [p128]

Increasing the geographical area covered by BCUs has had a significant detrimental impact.

Dispatch staff don’t recognise road names. Areas have vastly different crime issues, and local crime analysts no longer have the resources to develop intelligence about them. Alongside the loss of neighbourhood policing resources, this is increasing the distance between police and the communities they serve and making it harder to know the areas. [p128-129]

Rather than working with one local authority, BCUs now cover multiple local authorities, which makes strategic and operational coordination much more difficult.

On an very practical level,

Greater distances to travel have likely impacted response times. Logistically, the closure and loss of buildings such as custody suites has left police officers having to drive further to take prisoners to custody. There are personal impacts too, with officers having to walk considerable distances in the early hours of the morning to pick up cars after a change of shift. Officers described the ‘drift’ back to base, even avoiding calls and arrests, at the end of a shift. [p129]

At every level it's a complete shitshow.

In Neighbourhood Teams, the larger distances between wards and central bases particularly in larger areas, led to a commitment that no dedicated ward officer (DWO) would be more than a twenty minute away from their patch. This commitment was found to be unrealistic.

“It was changed to a 20 minute journey on public transport and then a 20 minute cycle ride. This supposed there are sufficient bikes for officers to use, which is not the case and also that all officers can use a bike and be made to cycle, which is also not the case.

The issue of bike availability was then compounded by the need for the bikes to be serviced on a yearly basis, regardless of use, by the provider Babcock. The service costs were prohibitive, which caused the fleet of bikes held to be rationalised. The contract is now with Halfords.” [p129-130]

This has led to more officers ending up in cars, but that also led to problems because of a lack of cars and of training to get officers to advanced, or even basic levels of qualification. This has been exacerbated by the pandemic which led to a curtailment of training. Drivers with advanced training end up being constantly on call, leading to at least one driver handing back his ticket to stop this.

The numbers of local instructors have also dwindled which has resulted in the Met spending a lot of money sourcing driving courses and instructors from across the country. Currently, officers are being sent to Wales to do a level three driving course. [p130]

Specialist teams operate outside BCUs and their elevated status which can cause problems as they are not accountable to the BCU chain of command.

This can undermine a BCU’s attempts to own its very extensive patch, and to be fully accountable for policing there, both to the Met and to the public.

“It’s the BCU that is held to account on performance for things that VCTF sometimes come in and wreak havoc on – not them.”

We were told that specialist teams tended to have rigid attitudes to their style of policing.

“Theirs is the right way and they do not want it questioned. This is particularly strong in firearms and public order where they are oriented towards national guidelines and ‘the way that they do things’. The impact on the community is immaterial.”

Officers described these teams as ‘parachuting in’. They argued TSG and VCTF are deployed on their boroughs without adequate liaison, without knowledge of local issues, and without sufficient sensitivity.

“TSG come here not knowing the area...they come late, allegedly go to the gym on job time...they annoy the community, and arrest people who probably didn't need to be arrested anyway...My colleagues think it suppresses crime. I don't think it's worth the community upset, it poisons the relationship with the community.”

[p131]

For anyone who's watched Brooklyn Nine Nine, this sounds reminiscent of the Vulture and I can only imagine how annoying it must be.

These specialist units seem to be so full of themselves they act with impunity. And they face no repercussions.

When concerns arise, the public and partners will go to the BCU as the police in charge of the area. However, they are not in charge of the specialist team and are unable to hold them to account. The Review was told of a ten-year-old Black boy who was removed from his garden and pinned to the ground by VCTF. When the boy’s family complained to the BCU Commander, we were told it took the BCU eleven working days to establish who had undertaken the search on his own BCU. There was no accountability and nothing the BCU Commander could do. [p132]

It is any surprise people like Couzens and Carrick thrive in these units?

The Met’s model of delivering policing operations is ‘centrally controlled, locally delivered’. The reality of this on the ground is that BCUs are frequently asked to deliver operations which are rolled out without building an understanding of the practical challenges associated with delivery, and how they might work for the local area. [p133]

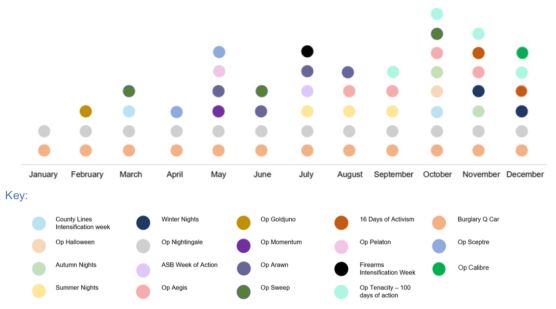

The number of operations that BCUs are supposed to promote is genuinely insane. The report shows this infographic, but notes, "This chart does not represent all operations; only those for which we have been given or identified a ‘frequency.’" [p133] and doesn't include one-off, often short-lived initiatives.

- Figure.4.6. Infographic showing the policing operations for BCUs organised by month.jpg (17.42 KiB) Viewed 18690 times

This level of central direction in local policing, and a patchwork and centrally-directed approach to addressing resourcing gaps, impacts on a BCU Commander’s ability to truly ‘own’ their local area, and to set their own direction and tone with their community. Commanders are constantly looking upwards, rather than downwards, and it becomes easy for public trust and confidence to be ignored. [p134]

The chapter concludes,

The closer the Met get to Londoners, the more beleaguered the service is. One sad aspect of this is that we frequently met officers who said they would worry if their fellow officers had to attend the homes of their parents, deal with their children or if they had family who were victims of crime. That in itself spoke volumes...

The demands of frontline policing in London’s communities should be the main driver for the whole service and the number one focus for the Met’s senior

management. Instead, it has allowed the frontline to degrade. However, despite an improvement in the Met’s finances in more recent years, and an uplift in police officer numbers, the Met has not yet taken sufficient measures to mitigate some of the most damaging consequences – in particular ensuring that those working on the frontline with the public are sufficiently trained, resourced and supported to do a good job and to listen to what they need. [p134-135]

It really feels like the Met is so enamoured with all its specialist units that it's forgotten what its fundamental role is. It's so focused on playing with cool toys and running around with guns that it looks down on those who do the 'boring' work. I really don't think it's a surprise that the worst sexual predators found (so far) are in these elite units. These units clearly see themselves as above 'normal' officers and their elevated status and the way they are protected from budget cuts makes them feel like they can act with impunity.