Long ramble about tanks, military aid, and the next few months.

Abrams are to be provided under Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative rather than Presidental Drawdown Authority Thread discusses some of the implications. Main upshot is they won't be there any time soon - probably done to preserve allocated Presidential Drawdown Authority for other uses.

There's pros and cons. Pros are that long term commitments are important, and people should stop thinking only about the short term. Also, these will be good condition, and likely very modern, and will come with training and appropriate support vehicles.

Cons are that it will take much longer to get them delivered. The other con is that the Americans are a f.cking terrible ally sometimes, and will remove the heavy armour modules from the tanks. This is a morally indefensibly move, and it's not like they are any great secret anyway - they are perforated armour made of depleted Uranium. Challenger 2s have similar modules, but in tungsten, and there's no suggestion that the UK's going to rip them out before delivering them. They aren't even an American developed concept - Chobham armour is a British development. The basic Chobham armour uses ceramics and a series of material transitions to defeat the metal penetrator jets from High Explosive Anti Tank warheads by disruption, as the brittle fractures of penetrated ceramic tiles leave jagged edges that put asymmetrical forces onto the jet and cause it to lose coherence. They are rather less effective against Kinetic Energy Penetrators, which is why the heavy metal modules are needed. These use the perforated armour concept, as by having some areas where there is extremely high resistance and some where there's very little resistance, the front end of the kinetic energy penetrator is deflected. Penetration is a factor of velocity and sectional density, which is why kinetic energy penetrators (image below) are very long and thin and made of exceptionally dense metal. If at even a slight angle, though, the effective sectional density radically drops. With the heavy metal modules, the Chobham armour on the front of an M1A2 Abrams or a Challenger 2 is designed to survive a hit from a Russian 125mm APFDS kinetic energy penetrator. Without it, it isn't. The reason western tanks have Chobham armour and Russian ones don't isn't because of any particular secret in its construction, it is because it is very difficult to actually make the stuff, and requires fairly advanced industrial technology, as to work optimally the ceramic tiles need to be under pressure from all directions, which makes assembling the modules a complicated process.

So the Leopard saga is an example of why perhaps its not best to buy German defence equipment. This is an example of why not to buy American.

So in the shorter term, Leopards and Challenger 2s are available. That still gives enough heavy armour to form a tank brigade or a couple of mechanised brigades, or to give heavy companies/battalions to several brigades otherwise equipped with former Soviet equipment. The question is how to use them most effectively. Training an entirely new force is likely to take too long to get them effective. Training is more important than the tank, up to a point, in effectiveness. On the other hand, Ukraine have a number of veteran brigades currently rebuilding their combat strength and not on the front line. Supplementing those crews with some newer recruits would be sensible, especially for the loaders, which Ukrainian forces currently don't have anyway. Of the tanks that

might get sent to Ukraine, only Leclercs have three crew and an autoloader, the rest have four crew, one of whom loads the gun. All Warsaw Pact tanks from the T-64 onwards have three crew and an autoloader. The manual loader can be an advantage, though. It allows safer ammunition storage, but it also allows a faster maximum rate of fire than a T-72 or T-90, which can be decisive. The T-64 and T-80 have faster autoloaders, but no faster than a reasonably skilled loader working hard, at least for the first few shots, and those are the ones that matter. In the First Tank Brigades heroic defense of Chernihiv, the faster followup shots possible with the T-64 were, along with better training and determination, cited as a factor in their defeat of the 41st Combined Arms Army with its T-72s. There's other advantages of western tanks that aren't talked about much by people too fixated on armour and guns; better gun depression (9 and 10 degrees for Challenger 2 and Leopard 2 respectively vs 4 degrees for a T-72), and also much better reverse speeds - over 30 kph vs just 4 for the T-72. The former is significant in defensive engagements, as being able to lower the gun further makes it easier to fight from a dug in position, or to improvise a hull down defensive position where the tank can fire at the enemy, but enemy fire cannot get at the tank's hull. The latter is significant because if a tank has to retreat under fire, it should do so in reverse so the thick forward armour is facing the threat. With just 4kph of reverse speed, a T-72 has to turn to retreat, exposing the thin rear armour.

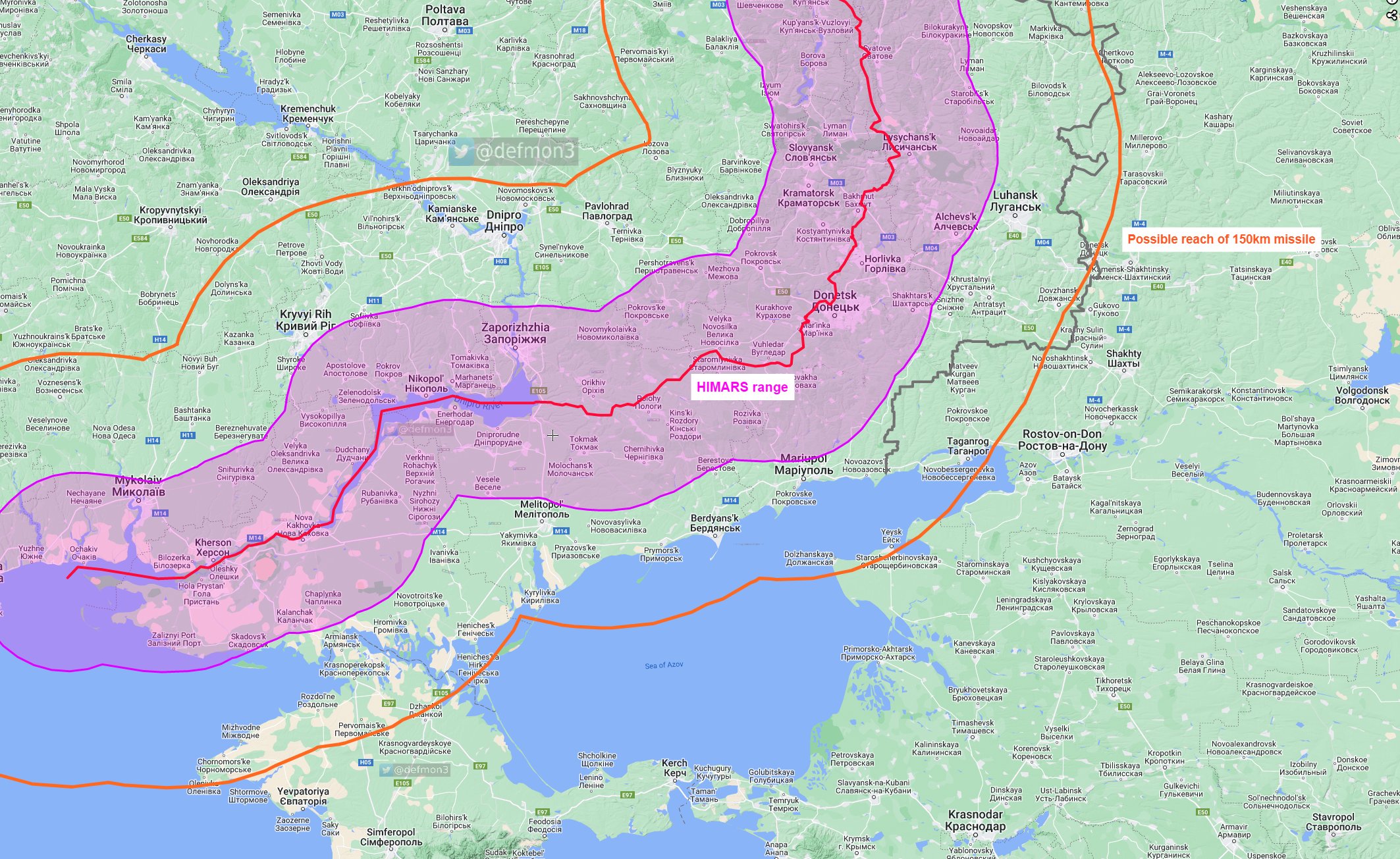

It probably makes the most sense to assign the western tanks to some of the best units, like the aforementioned First Tank Brigade, even though it will in the short term see them out of action with training. Once that bump's overcome, though, they will get the best return and give a bigger payoff for the logistical challenge. They'll probably see action fairly concentrated too, and we saw a lot of new western kit concentrated for september's very successful Kharkiv offensive. The concern is that all the western equipment going to one place rather telegraphs Ukrainian intentions, but then they managed to conceal the Kharkiv offensive force until it struck - it's a lot easier of course when the trees are in leaf. The former Warsaw Pact kit will get harder to maintain over time, and Ukraine's own tank production is almost certainly dead, as the factory in Kharkiv was hit, and the castings apparently came from Azovstal. There's still quite a lot of life in most of it, though, and it won't be wasted. I'd expect to see kit displaced from the units that get western equipment - APCs and IFVs and support vehicles as well as tanks - to go to the northern border, where it can guard against an unlikely attack through Belarus while new crews get up to speed.

There's quite a bit of talk about a potential Russian offensive soon. I think one is likely. I think claims that they'll attack through western Belarus and aim for Lviv with hundreds of thousands of new conscripts are b.llsh.t, but some new offensive is likely, most likely in the Donbas or the south, as an attack through Belarus would have to contend with the Pripet marshes and extensive Ukrainian defensive works and minefields, and if they went further west their flank would be open to Poland, and a political miscalculation - remember such an attack would be seen as a massive escalation - could bring in the well-equipped Polish army. A more modest mobilisation is certainly possible, the thing to bear in mind is that a smaller mobilisation won't bring in a decisive number of bodies, and the larger a mobilisation is the more people will flee Russia, the more workers won't be at work, and the faster the already teetering Russian economy will fail. Conscription and mobilisation also do not generate soldiers, they generate bodies that need to be turned into soldiers, a process for which Russia relies on existing troops to act as instructors, with training largely done in unit. That would be rather hampered by the very severe casualties Russia has taken to date.

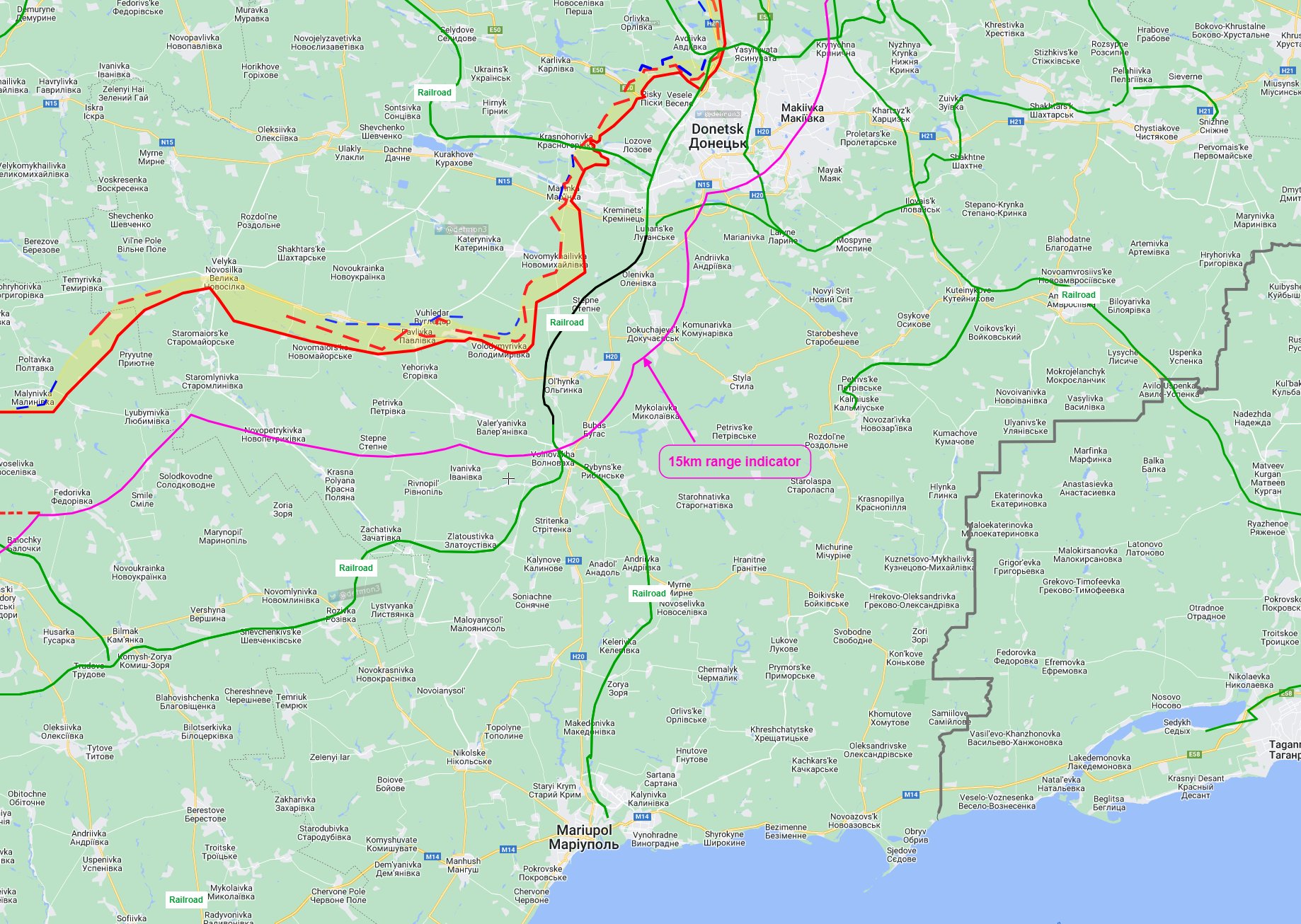

Ukraine are also likely to want to plan an offensive, but for several reasons it makes sense to wait until the Russians have had their go, so to speak. Keeping the best units in reserve to counter-attack reduces the odds of a significant Russian success, and so long as Ukraine can deny the Russians the chance to breakout and manoeuvre, as they have since late spring, the Russians will likely suffer significantly more casualties and loss of materiel than the Ukrainians, which would make a subsequent Ukrainian offensive easier. This is particularly the case as Russian tactics continue to devolve and rely more and more on large, poorly supported infantry formations.

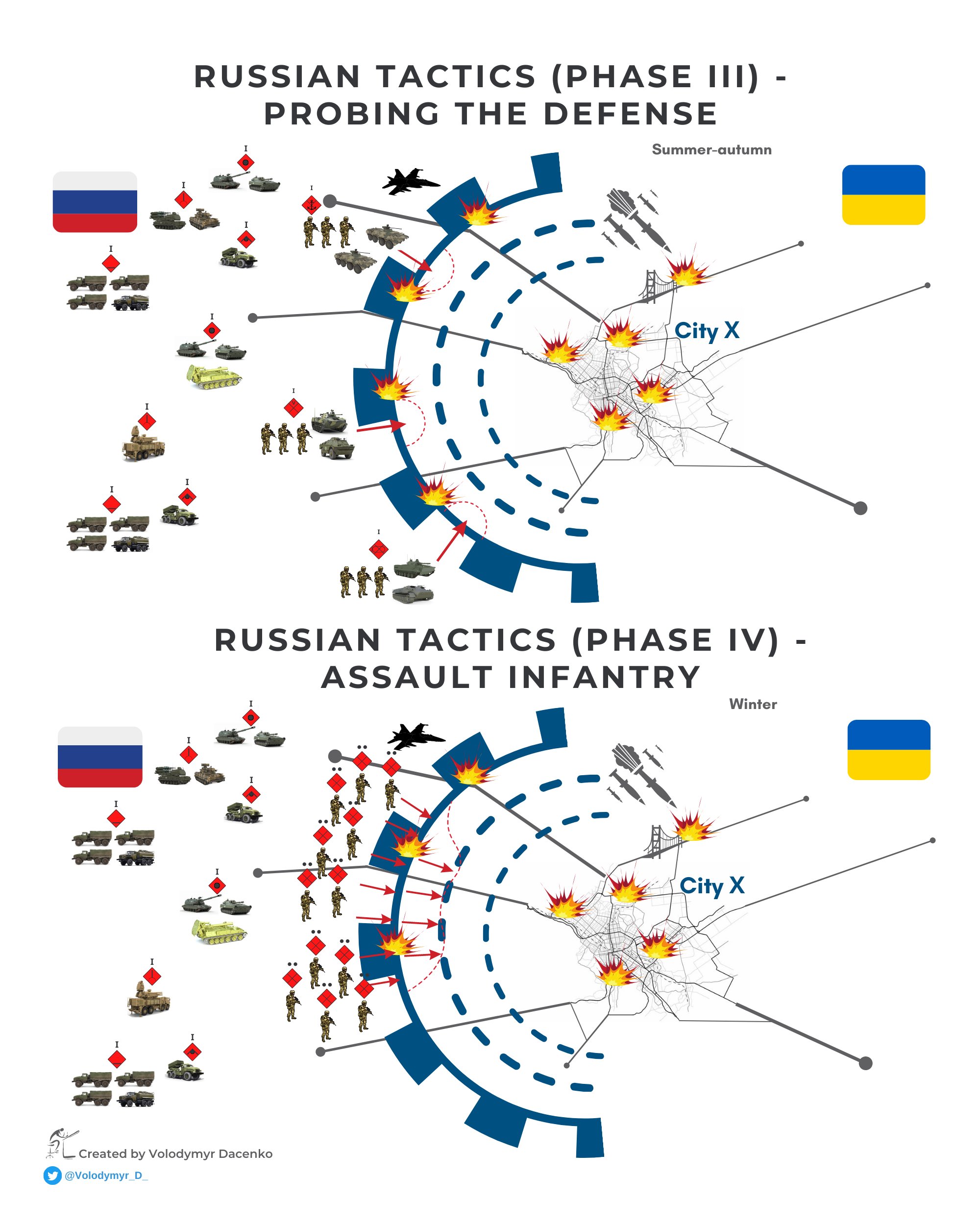

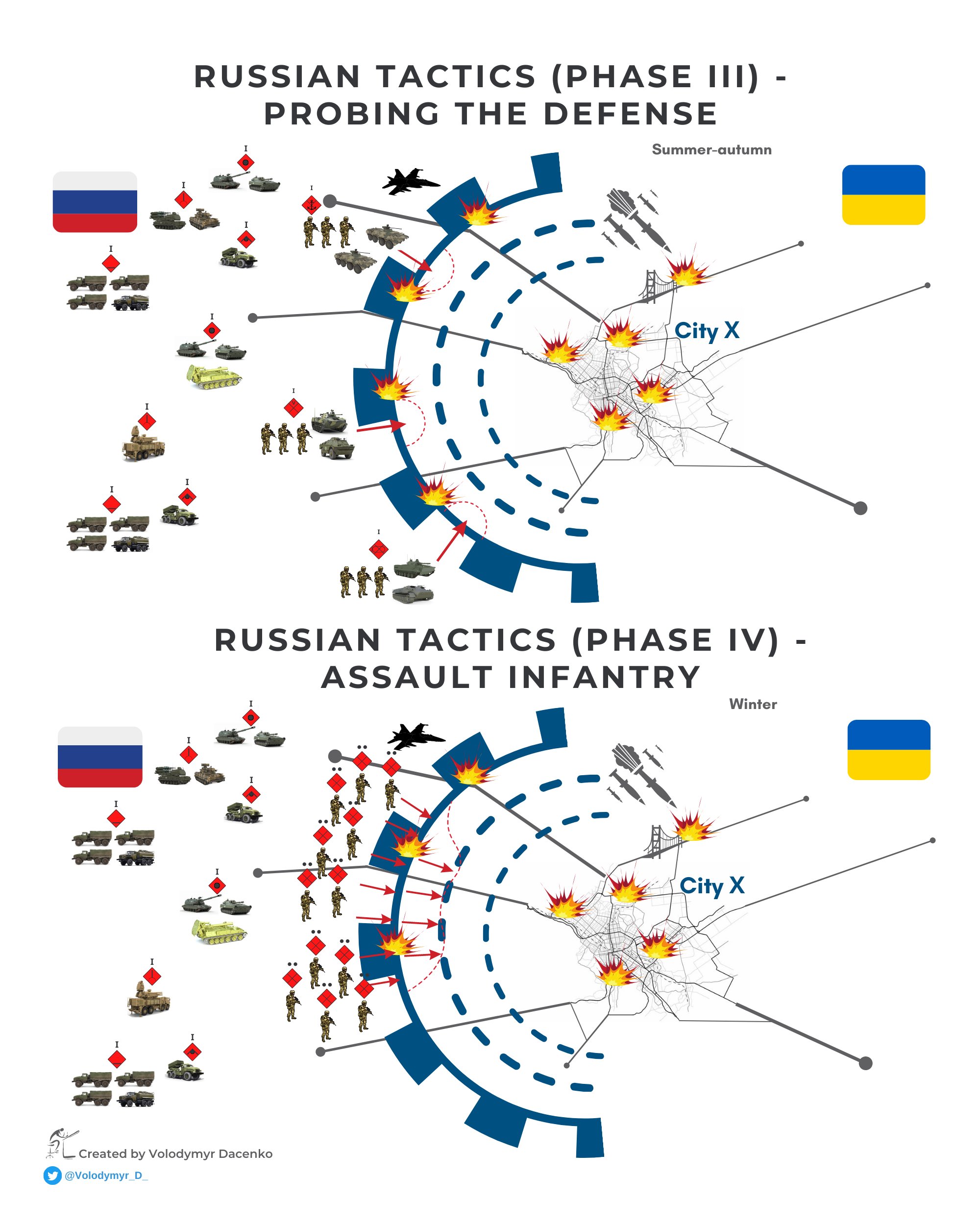

This excellent thread discusses their tactical changes in detail from the start of the war to the present. I thoroughly recommend reading it, and include its initial graphic below.

ETA: the tactical change image was actually two images, so adding the second one as well